CORVALLIS, Ore. (KOIN) — Researchers with Oregon State University revealed a three-dimensional fluid model that gives new insight on seismic activity in the Pacific Northwest.

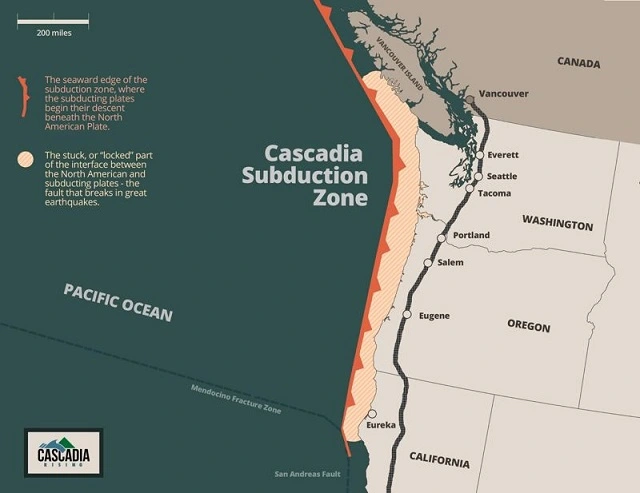

According to OSU, the model shows fluid stored deep in Earth’s crust along the Cascadia Subduction Zone. It provides new information into on how the accumulation and release of those fluids may influence seismic activity in the area. Gary Egbert, an electromagnetic geophysicist in Oregon State’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, said the pressure associated with these fluids could be a factor in the seismic phenomenon known as episodic tremor and slip and these findings have applications for helping people understand seismic activity.

“Water is a key player in both seismic activity and volcanism in Cascadia,” he said. “This is a new view of these fluids. It’s information that could be used in conjunction with other data, and more detailed model studies, to better understand large earthquakes in Cascadia.”

The fluid collects near but does not penetrate a thickened section of the crust that lies beneath much of western Oregon and Washington, explained the university.

Egbert is also a lead author of a new paper detailing the findings, which were published in the journal Nature Geosciences.

“Episodic tremor and slip is a fault behavior that includes both localized non-volcanic tremors and slow-slip events that may occur over hours or days,” said Oregon State University in an announcement. “It occurs throughout the Cascadia Subduction Zone, from northern California to British Columbia, but is less frequent and intense beneath the central core of Siletzia, which runs primarily under the Oregon Coast range and ends near Roseburg.”

The geophysicist’s paper takes from decades of work to collect magnetotelluric data – both offshore and on land – throughout the Cascadia Subduction Zone. OSU described Magnetotellurics as a geophysical technique that uses surface measurements of magnetic and electric fields to reveal subsurface variations in electrical resistivity.

“Most solid rocks don’t conduct electricity very well, but dissolved solids cause water to be conductive, so the magnetotelluric data can be very useful for detecting where water exists in the subsurface,” said Egbert.

Water naturally cycles down from the ocean into the Earth’s crust, where it accumulates and chemically combines with minerals, explained the university. This is where the oceanic crust is thrust beneath the continent along subduction zones. It then heads up and releases water.

The released fluids can weaken crustal rocks, added OSU, leading to a crustal deformation. This can be both from slow-release stress, such as with episodic tremor and slip, and from very large, damaging earthquakes.

Egbert said better knowledge of the subsurface fluid distribution is extremely relevant to evaluating seismic hazards in areas such as Cascadia, where there is significant potential for a catastrophic megathrust earthquake.

Using software created by Egbert and his colleagues, the magnetotelluric data allowed the researchers to create a detailed three-dimensional view of where fluids are stored within the Cascadia forearc, which is the area between the ocean trench and its associated volcanic arc.

The three-dimensional imaging allows researchers to see fluids accumulate more directly and draw inferences about their movement, according to the announcement.

It added that the new images show fluid trapped in elongated sheets that run parallel to the coastline and reveal areas where underthrust sediments are piling up against impenetrable volcanic rock that stores little water.

Beneath the core of Siletzia, said OSU, the storage and transport of fluid is more focused within a narrow subduction channel that exhibits less episodic tremor and slip.

“The results demonstrate how the deep roots of Siletzia are critical to how fluids are transported and where they pond within the subduction zone,” said co-author Paul Bedrosian of the U.S. Geological Survey. “The implications of this for understanding seismic variability in Cascadia is just starting to be recognized.”

However, more research is needed to understand the relationship between these fluids and earthquakes along the Cascadia, but that work is not out of reach, Egbert said.

“It’s a complicated problem, but ultimately there is potential application for interpreting this information in conjunction with seismic data and geodynamic modeling to determine the relationship between fluid storage and movement and seismic events,” he said.